Bantu Education was a system of schooling in South Africa during apartheid. It began in 1953 and was designed to separate black and white students. Black students were given an inferior education with limited opportunities. The government aimed to keep black people from getting the same education as white people.

This system was unfair and hurt the future of black children. Bantu Education was widely criticized, and many people fought against it. Eventually, it was replaced with a more equal system after apartheid ended in 1994, allowing all South African children the same educational opportunities.

The unparalleled importance of civic education in today’s society has played a major role, as it has helped developing societies to rise up and take the initiative of stopping every unfavorable policies. One of the threads of segregating policies is that of the Bantu education act, which we’ll discuss in detail in this article.

What Is Bantu Education?

Bantu education was a type of school system in South Africa during apartheid. It was designed to separate and discriminate against black South African students. They received a lower quality education than white students. It was a way to control people of color by limiting their opportunities for learning and advancement.

Brief History Of Bantu Education

In 1949, the government established the Eiselen Commission to assess the state of African education. The Commission recommended implementing radical measures to reform the Bantu school system effectively.

By 1953, before the enactment of the apartheid government’s Bantu Education Act, 90% of black South African schools received state aid and were mission schools. The Act mandated that all such schools must register with the state, thereby removing control of African education from churches and provincial authorities.

This authority was centralized in the Bantu Education Department, which was committed to maintaining a separate and inferior educational system. As a result, nearly all mission schools closed down, with the Roman Catholic Church being one of the few attempting to continue operating without state assistance.

The 1953 Act also separated education financing for Africans from general state funding. It tied it to direct taxes paid by Africans, leading to significantly less spending on black children than white children.

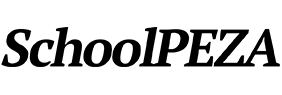

In 1954-1955, black teachers and students protested against Bantu Education, forming the African Education Movement, which aimed to provide alternative education. Cultural clubs briefly operated as informal schools, but by 1960, most had closed down.

The Extension of University Education Act, Act 45 of 1959, prohibited black students from attending white universities, instead creating separate “tribal colleges” for black university students. This policy further segregated tertiary education based on race, with institutions like Fort Hare, Vista, Venda, and Western Cape being established. This restriction on attending white universities prompted strong protests.

Also Read: What is Citizenship Education? All You Need to Know

Expenditure on Bantu Education increased in the late 1960s as the apartheid Nationalist government recognized the need for a trained African labor force. While more African children attended school than under the old missionary education system, they were still severely deprived of facilities compared to other racial groups, especially whites.

Nationally, the pupil-to-teacher ratios increased from 46:1 in 1955 to 58:1 in 1967. Overcrowded classrooms were utilized rotating, and there needed to be more qualified teachers. In 1961, only 10% of black teachers held a matriculation certificate (equivalent to the last year of high school). Black education was essentially regressing, with teachers less qualified than their students.

The Colored Person’s Education Act of 1963 controlled “colored” education under the Department of Colored Affairs. “Colored” schools also had to be registered with the government, separating “colored” education from white schooling.

In 1965, the Indian Education Act was passed to segregate and regulate Indian education, placing it under the Department of Indian Affairs. In 1976, the South African Indian Council (SAIC) assumed certain educational functions and Indian education became compulsory.

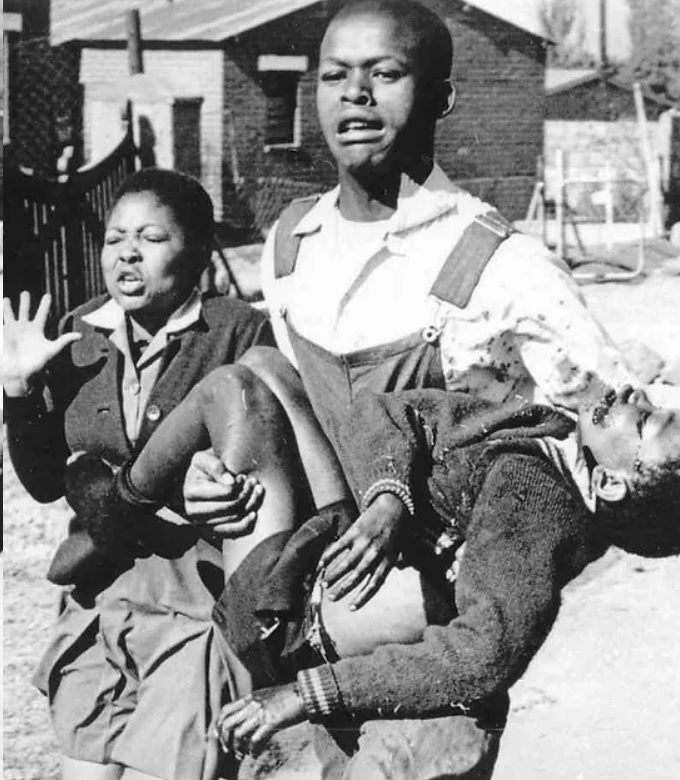

Due to the government’s “homelands” policy, no new high schools were constructed in Soweto between 1962 and 1971. Students were encouraged to relocate to their homelands to attend newly built schools. However, in 1972, the government yielded to pressure from the business sector to improve the Bantu Education system to meet the demand for a better-trained black workforce.

As a result, 40 new schools were established in Soweto. Between 1972 and 1976, the number of secondary school pupils in Soweto surged from 12,656 to 34,656, with one in five Soweto children attending secondary school.

The Bantu Education Act, 1953

A South African legislation that came into effect on January 1, 1954, was a pivotal component of the apartheid system, which endorsed racial segregation and discrimination against nonwhite individuals within the nation.

Before its enactment, most schools catering to Black students were administered by missions and often received state support. However, many children did not have access to these educational institutions.

In 1949, the government established a commission, led by anthropologist W.W.M. Eiselen, to assess and propose recommendations for educating native South Africans. The Eiselen Commission Report of 1951 recommended that the government assume control of education for Black South Africans, integrating it into the broader socioeconomic plan for the country.

Furthermore, the report emphasized the importance of tailoring the curriculum to reflect the needs and values of the local communities. The Bantu Education Act largely adhered to the commission’s recommendations.

Under this act, the Department of Native Affairs, under the leadership of Hendrik Verwoerd, assumed responsibility for the education of Black South Africans with the establishment of the Department of Bantu Education in 1958. Black children were mandated to attend government schools, where instruction was primarily delivered in their native languages, though English and Afrikaans were also part of the curriculum. The subjects included needlework for girls, handcraft, agriculture, soil conservation, arithmetic, social studies, and Christian religion.

This education was designed to prepare children for manual labor and menial jobs, as dictated by the government’s view of their role. It aimed to foster the idea that Black people should accept subservience to white South Africans. Funding for these schools came from taxes collected within the communities they served, resulting in significantly less financial support than white schools. Consequently, a severe shortage of qualified teachers led to high teacher-student ratios ranging from 40 to 1 to 60 to 1.

Efforts by activists to establish alternative schools, referred to as cultural clubs because they were illegal under the Education Act, had collapsed by the end of the 1950s.

High schools were initially concentrated in the Bantustans, designated as homelands for Black South Africans. However, during the 1970s, the demand for better-trained Black workers prompted the establishing of high schools in areas like Soweto, just outside Johannesburg. Nonwhite students were denied access to open universities by the Extension of University Education Act (1959). The Bantu Education Act was eventually replaced by the Education and Training Act 1979.

Mandatory segregation in education ended with the passage of the South African Schools Act in 1996. Nonetheless, decades of inadequate education and barriers to entry into historically white schools had left most Black South Africans significantly disadvantaged in educational attainment by the beginning of the 21st century.

Related: Short Bantu Education Act Essay 300 Words

Effect Of Bantu Education

The Bantu Education Act from a long time ago still affects South Africa today in several ways. Let’s look at ten of these effects that are still noticeable.

1. Unequal Education: In the past, black South Africans didn’t get the same quality education as white South Africans. The Bantu Education Act created this unfair system.

2. Skills Gap: Because of this law, many black South Africans didn’t learn the skills they needed for today’s jobs. This is one reason why some people can’t find work.

3. Unemployment: High unemployment in South Africa is partly because of the Bantu Education Act. It made it hard for people to find jobs or start businesses.

4. Poverty: Many South Africans are poor because they couldn’t get a good education. This law also made racial and economic gaps bigger.

5. Political Troubles: The Bantu Education Act stopped black South Africans from participating in politics and thinking critically. This led to protests and violence against apartheid.

6. Limited Access to College: This law made it tough for black students to attend college. Today, there are still not enough black students in universities.

7. Language Barriers: The Act made students learn in their home languages rather than in English or Afrikaans. This made it hard for some students to get into college and created language divides.

8. Cultural Loss: The Bantu Education Act tried to erase traditional African culture. Students had to give up their customs and languages to fit into the Western system.

9. Limited Social Mobility: Black South Africans couldn’t get a good education or better jobs because of this law. This also hurt the growth of the black economy.

10. Inter-generational Impact: The effects of the Bantu Education Act still affect many black South Africans today, as they couldn’t access good education or opportunities.

So, even now, South Africa still deals with the consequences of the Bantu Education Act, which has left a lasting mark on the country.

Questions And Answers Based On the Bantu Education Act,

The Bantu Education Act was a piece of legislation in South Africa that had significant implications for the education of black South Africans during the apartheid era. Here are answers to your questions:

What was the Bantu Education Act?

The Bantu Education Act was a South African law that established a segregated and inferior education system for black South Africans during the apartheid era. It aimed to provide education for black people that would prepare them for a subordinate role in society, primarily as laborers.

When was the Bantu Education Act enacted?

The Bantu Education Act was enacted in 1953.

Who proposed the Bantu Education Act, and why?

The South African government proposed the Bantu Education Act, particularly by Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, the Minister of Native Affairs at the time.

The motivation behind the act was to entrench and reinforce racial segregation and apartheid policies in South Africa, with a specific focus on controlling and limiting the educational opportunities available to black South Africans.

What were the main provisions of the Bantu Education Act?

The Bantu Education Act included provisions that:

- Established a separate and inferior education system for black South Africans.

- Promoted local languages in education, limiting the development of English or Afrikaans language skills.

- Emphasized vocational and manual training over academic and intellectual education.

- Controlled the content of textbooks and curricula to support apartheid ideologies.

How did the Bantu Education Act affect black South Africans’ access to education?

The act severely restricted access to quality education for black South Africans. It created an underfunded, understaffed system and lacked proper resources and infrastructure. This led to an education system that did not adequately prepare black students for meaningful social and economic participation.

What were the goals and motivations behind the Bantu Education Act?

The main goals were maintaining white supremacy, enforcing racial segregation, and perpetuating apartheid policies. The government aimed to prepare black South Africans for a subservient role in society and prevent them from receiving an education that could challenge the apartheid system.

How did the Bantu Education Act contribute to racial segregation in South Africa?

The act formalized and deepened racial segregation by creating a separate and unequal education system for black South Africans. It further entrenched apartheid policies by segregating children along racial lines from an early age.

How did the Bantu Education Act differ from the education system for white South Africans during apartheid?

White South Africans had access to a well-funded, high-quality education system emphasizing academic and intellectual development. In contrast, under the Bantu Education Act, black South Africans received a far inferior education, focusing on vocational and manual training, limited resources, and an emphasis on segregation.

What were the long-term consequences of the Bantu Education Act on South African society?

The Bantu Education Act had profound and lasting effects on South African society. It contributed to educational inequality and limited opportunities for black South Africans. This inequality continues to impact generations, hindering socio-economic advancement and perpetuating disparities.

When and why was the Bantu Education Act repealed?

The Bantu Education Act was officially repealed in 1979, although reforming the education system began in the 1970s. The repeal was part of broader changes in South Africa’s apartheid policies and marked the beginning of dismantling apartheid.

The government recognized the need for educational reform to address social and political unrest and to work toward a more inclusive and just society.

Bibliography Of Bantu Education Act (1953)

Ahmed, M. 1990. Literacy and development: Moving from rhetoric to reality. Paper read at the International Seminar on Literacy in the Third World, 6-7 April 1990, Commonwealth Institute, London.

Aitchison, J. 2001. ABET on Trial. EPU Quarterly Review of Education and Training in South Africa, Vol. 8(1).

Aitchison, J., Houghton, T. & Baatjes, I. (Eds.). 2000. University of Natal survey of adult basic education and training: South Africa. University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg: Centre for Adult and Community Education.

Auerbach, F. 1989. Eradicating illiteracy. Matlhasedi Education Bulletin, 8(1/2, Nov/Dec). Mmabatho: University of Bophuthatswana.

Bataile, L. (Ed.). 1976. A Turning Point for Literacy: Proceedings of the International Symposium for Literacy, 3 to 8 September 1975, Persepolis, Iran. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Baynham, M. 1995. Literacy practices: Investigating literacy in social contexts. London: Longman.

Behr, A.L. 1963. Onderwys aan Nie-Blankes. In Coetzee, J.C. (Ed.). Onderwys in SuidAfrika 1652-1960. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Bantu Education (Conclusion)

Bantu Education was a system of schooling in South Africa that was designed to separate and discriminate against black students. It was a very unfair and harmful system that limited opportunities for black people. Despite the challenges, black students and their families fought against this unjust system and showed their resilience and determination to gain the education they deserved. Today, South Africa is working to provide equal and better education opportunities for all its citizens.